No Poverty Reduction Without Disaster Resilience: Pass the PRESENT Bill!

January 19, 2026 | Bicol Mail

For twelve years, the past has come to the present. This phrase captures the long and unfinished legislative journey of the bill on social enterprises with the poor as primary stakeholders—from its early incarnation as House Bill No. 6085 during the 15th Congress (2012–2013), widely known as the Magna Carta for Social Enterprises, to what is now the Poverty Reduction Through Social Entrepreneurship (PRESENT) Act.

That earlier bill, formally titled An Act Promoting Social Enterprises with the Poor as Primary Stakeholders (SEPPS) and Providing Incentives Therefor, was filed by Senator Sonny Angara. Its purpose was straightforward yet transformative: to institutionalize social enterprises as a deliberate, long-term strategy for poverty reduction. Although it did not become law, the bill introduced a powerful policy idea—that poverty reduction is not only about welfare transfers, but also about enabling the poor to become co-owners, producers, and decision-makers in viable enterprises.

From 2016 onward, the advocacy did not fade. Instead, it evolved into what is now known as the PRESENT Bill. The shift in framing—from a “Magna Carta” to “Poverty Reduction Through Social Entrepreneurship”—reflected a deeper recognition that social enterprises are not marginal actors at the fringes of the economy. They are central to inclusive growth, value-chain upgrading, and community-based development, particularly in contexts where markets and state services fail to reach the poorest.

Sustaining this continuity has been a broad alliance of advocates known as the PRESENT Coalition. Under the leadership of the Institute of Social Entrepreneurship in Asia, led by its founder Lisa Dacanay, the Coalition has consistently articulated the bill’s core pillars. These include a clear and operational definition of social enterprises with the poor and marginalized as primary stakeholders; the creation of a national PRESENT Program with defined planning and implementation mechanisms; and a coherent set of incentives and benefits such as tax relief, preferential access to financing, market support, and capacity-building.

Equally central is the establishment of a Social Enterprise Development Fund or similar financing mechanisms. Such a fund would provide seed capital, credit lines, and emergency stimulus, recognizing that social enterprises are wealth-creating organizations that pursue social missions in ways that must be financially and ecologically sustainable. Over time, refinements to the bill have also incorporated preferential procurement and market access for social enterprises, stronger inter-agency coordination through a Social Enterprise Development Council, and special recovery and rehabilitation support for enterprises affected by disasters and extreme events.

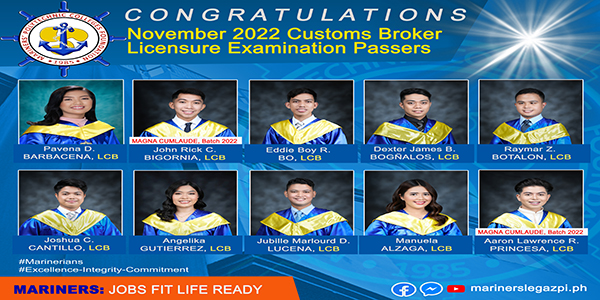

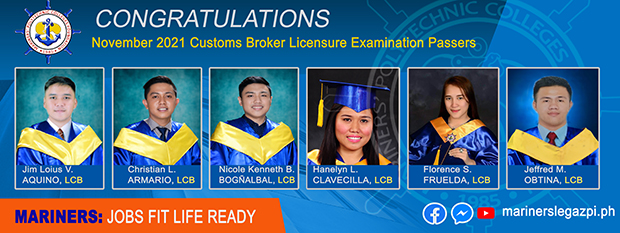

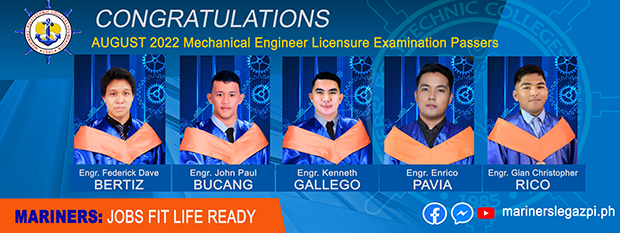

In 2024, the Tabang Bikol Movement (TBM), a regional volunteer network for disaster resilience and sustainable development, joined the PRESENT Coalition. This followed a Regional Social Enterprises Summit convened with TBM partners from the Mariners Polytechnic Colleges Foundation, Central Bicol State University of Agriculture, Bicol University, Naga College Foundation, and Bicol State College of Applied Sciences and Technology, with research support from the Commission on Higher Education.

TBM’s engagement reflects a crucial policy insight: poverty reduction and disaster resilience can no longer be treated as separate agendas. Climate-related disasters—typhoons, floods, droughts, and sea-level rise—disproportionately affect the poorest communities. These are the same communities that social enterprises serve, employ, and organize. Because they are locally embedded, socially accountable, and adaptive, social enterprises can often respond faster than large institutions. They are uniquely positioned to protect livelihoods, maintain access to essential goods and services, and support community-level recovery.

As the Coalition pushes for the bill’s passage, the challenge is how to strengthen its disaster-resilience dimension without prolonging the legislative process. A strategic entry point already exists in Chapter II, Poverty Reduction Through Social Enterprise, particularly Section 6 on the formulation of the PRESENT Program. This section enumerates guiding principles such as people’s participation, sustainability, gender sensitivity, and the development of accessible social services for the poor.

Adding an eighth principle—on disaster resilience and climate responsiveness—would be both efficient and impactful. This would ensure that social enterprises are enabled to anticipate, reduce, and manage disaster and climate-related risks; protect livelihoods and productive assets of marginalized sectors; maintain continuity of operations during crises; and contribute to community resilience and recovery. It would also reduce long-term government relief costs, align enterprise development with national disaster risk reduction and climate policies, and prevent repeated cycles of poverty triggered by disasters.

By embedding disaster resilience as a guiding principle, all implementing actors—from national agencies to local governments—can move in step. In doing so, the PRESENT Act becomes not only a pathway out of poverty, but a forward-looking instrument that equips social enterprises, and the communities they serve, to withstand and recover from an increasingly uncertain climate future

From Pandesal to Oil: Two Ways of Earning

January 9, 2026 | Bicol Mail

Every morning along our street on Misericordia, near Panganiban in Naga City, a familiar voice glides ahead of the day. It comes from a sound system mounted on a humble tricycle, looping like a gentle alarm clock: “Yaon na po, malunggay pandesal, masarap na, mainit pa.”

Since the pandemic, it has made its rounds faithfully, announcing not just bread but routine—proof that mornings still arrive, warm and reliable.

The pandesal on wheels now crisscrossing Naga City and much of Camarines Sur traces its roots to Masbate, another poor Bicol province. As early as 2019, before the pandemic, pandesal makers there began teaching one another how to bake and sell bread from rolling tricycles. Now they have penetrated every town and city not only in Bicol but Mindanao and the Visayas. According to Arnel Daitol of Camaligan, it was—and remains—a collective struggle. Vendors wake at 4:00 a.m. to mix dough, bake through the dark, load bread by sunrise, and sell until sundown. It is poverty resisted the hard, honest way, learned neighbor to neighbor, without fanfare or guarantees.

The tricycle rolls by with its small glass-fronted case, shelves layered with hot pandesal. Steam fogs the panes. Today’s batch is flecked green—malunggay folded into the dough—each roll hiding a small cube of cheese that softens when torn open. You smell it before you see it: yeast, butter, warmth, comfort. It is food that answers a simple human need.

That morning, I was supposed to be writing my Bicol Mail column on a post–New Year event—the U.S. attack on Venezuela over the weekend of January 3. But the repeated taped call of the pandesal vendor outside caught my attention, and my hunger.

Suddenly, the contrast was unavoidable.

Here was the most immediate need of the moment: hot bread promised honestly and delivered by hand. And there was Venezuela—its oil coveted from afar, wealth pursued not by making something, but by taking control of what already exists.

From Pandesal to Oil: Two Ways of Earning, Two Moral Worlds. That felt like the right frame.

From our window, I watched the vendor steady his rolling store. Long before most of the city wakes, he has already worked for hours. The pandesal worker rises in darkness to mix flour, yeast, water, and effort into dough. By sunrise, the bread is baked, loaded, and sold street by street. Income is uncertain but bigger than most on average. Weather, competition, and appetite decide the day. But the labor is real. What he earns comes directly from sweat, skill, and time.

This is money made the hardest way: by producing something useful and offering it to the community. It is the quiet story behind the hundreds—now thousands—of pandesal vendors across Naga, Bicol, and the country. They do not speculate. They do not extract. They work, sell, and hope.

Now place this beside another way money is made.

When powerful states or corporations intervene in countries like Venezuela to control oil resources, wealth is generated not through personal labor but through power—over land, politics, and people’s futures. Oil is not created by those who profit most from it. It already exists beneath the ground. Control is gained through sanctions, economic pressure, political manipulation, or force. Risks are pushed downward to ordinary citizens; profits flow upward and outward.

You may say this is getting political. It isn’t. It’s economics—and morality.

The pandesal vendor creates value from almost nothing. Flour becomes bread. Bread becomes breakfast. If no one buys, there is no income. Risk is personal. Dignity lies in work. Resource exploitation works the opposite way. Wealth comes from appropriation rather than production. What is taken is not just oil, but a people’s ability to decide how their resources should shape their own future.

Both are called “earning,” but they do not belong to the same moral universe. The pandesal worker takes nothing from anyone else to live. No community is displaced. No sovereignty weakened. His success depends on trust and mutual need. The bread feeds the neighborhood. The other feeds an appetite that is never full—driven by an energy-hungry global system now scrambling for supply, with Venezuela’s vast heavy crude reserves once again in its sights.

If we truly value hard work, we must be honest about what counts as work. Getting up at dawn to bake bread is work. Rolling through the streets for small change is work. Rearranging global systems so wealth flows from the weak to the powerful is extraction. It is foreign intervention.

The voice calling “malunggay pandesal, mainit pa” reminds us of a moral economy we understand instinctively: you earn by contributing. If we want a just world, we should listen more closely to that sound in the morning—and be far more critical of the silence that follows when a nation’s resources are taken in the name of profit.